Tabby, also called plain

weave, is the most basic of weave structures and a great place to start for new

weavers. For my first weaving project, I

decided I use to use the small 24 inch rigid heddle loom I already had, and

work with tabby (partly because rigid heddles work best for tabby and partly because

I had almost no prior weaving experience).

The basic structure is very

simple. The weft threads travel over

every other warp thread, alternating each row to create the weave. This can be achieved with finger manipulation

or needle weaving, but the rigid heddle makes manipulating the warp threads

much quicker and simpler, allowing the weaving to raise or lower the threads

all in one motion. The primary

disadvantage to this style of loom (aside from having only one heddle or shaft)

is that the heddle is free-floating and doubles as the beater, making it

difficult to maintain an even beat and keep the selvedges straight.

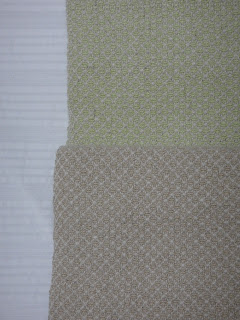

The cloth was tabby woven

using a rigid heddle loom at 10 DPI at the full loom width of 24 inches. After

weaving, the cloth was fulled in a washing machine. Pre-fulling, the weave was

quite open and relatively even, though some areas were packed more tightly than

others (this was my first major weaving project and the first time I had worked

with a wool warp, so there was a bit of a learning curve in this process).

After fulling, the weave evened out a great deal and packed down considerably.

By the end of the fulling and dyeing process, the warp and weft were barely

visible and a compact, water repellent fabric had been produced, as can be seen

in the finished piece. This is significantly thicker and denser than the cloth

used in the extant Dublin caps, but will serve as a useful warm layer at cold

and wet events.

The cloth used to make my

Dublin-style Viking hood had been intended for another project, but due to

excess shrinkage in the fulling and dyeing process was not suitable for my

intended use (a later period hood). After making a pair of mittens out of part

of the length of fabric, I had a piece left which was just large enough to make

this cap if I placed the fold along the back of my head rather than across the

top (kismet!). As conservation of resources seems within the spirit of the time

period, this alteration of the basic pattern seems to be plausible if not

entirely supported by the archeology in Dublin and Jorvik.

Of the twelve caps and three

remnants of caps studied in Heckett, nine of the caps and two of remnants are

wool. All of the examples are tabby woven, with an even weave structure. All

but one are classified as having an open weave. The wool caps are woven at a

range of 12 to 23 warps per centimeter, with wefts ranging from 9 to 20 per

centimeter. The cloth for all of the caps is lightweight and quite fine, and

some of the silk is very delicate. At least some of the hoods seem to have been

purpose-woven on narrow warps. All of the wool caps analyzed in Heckett have

selvedges along two sides, while the silk caps all appear to have been cut to

size from wider pieces of cloth. Most have not been analyzed for dye, but of

those that have two were undyed, two showed traced of iron mordant.

Sources:

Heckett, Elizabeth Wincott. Viking

Age Headcoverings from Dublin. Royal Irish Academy, 2003.

Walton, Penelope Textiles, Cordage and Raw Fibre from 16-22 Coppergate,Council

for British Archaeology, London, England 1989.

Viking Silk Cap,

Yorkshire Museum

(http://www.historyofyork.org.uk/themes/life-in-viking-york/viking-silk-cap).

Crowfoot, Elisabeth. Textiles

and Clothing c.1150-c.1450. Medieval Finds from Excavations in London, 4.

London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1992.